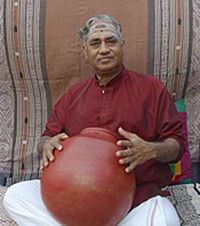

Konnokol originates from South India. It is a rhythmic musical language made up of meaningless one syllable sounds that function as a map to navigate South India’s three major drums, the Mridagam, Ghatam and Kanjira. Konnokol is also a means to catalogue all the compositions for those drums that exists within the South Indian Carnatic classical musical tradition.

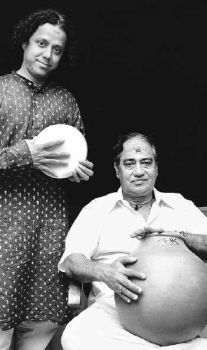

Since India’s musical traditions are oral traditions, it follows that Konnokol is a musical language. It is also performed simply by being sung and functions on its own as a percussive art form simply expressed through the human voice. Indeed, though less common, some South Indian musicians specialize in Konnokol only, without actually applying it to playing an actual drum; or, are recognised as Konnokol masters, as is the case with my teacher Subash Chandran from Chennai Tamil Nadu.

Have a listen to Subash Chandran here

As one would expect from any system or methodology associated with an Indian musical tradition, the system of Konnokol functions at a radical musical depth, and has profound pedagogical implication for students of rhythmic phrasing associated with any tradition. The Indian tradition explores great subtleties and nuance; it leaves no stone unturned with what the universe offers us in terms of the possible numeric calculations existing within the realm of its aesthetic musical paradigm.

In my opinion, this system is the most advanced and yet straightforwardly simple rhythmic methodology based on internalising rhythmic form through lingual musical language while keeping time through “thalam” (hand claps and waves) that exits on the planet to date. It can be applied in learning to count and phrase rhythmically the subdivisions and time signatures found within all musical traditions.

Indeed, it seems to me that learning Konnokol is of primary significance in all musicians lives regardless of tradition, since it represents the very foundation, the rhythmic building blocks that underpin all music’s and musical traditions.

So what are these musical phrases, well if we took numbers 1 though to 9 they would be written as follows:

1 = TA

2 = TA KA

3 = TA KA TA or TA KI TA

4 = TA KA TE MI

5 = TA TI KE TA TOM

6 = TA KA TA KA TE MI

7 = TA KA TA TA KE TE MI

8 = TA KA TE MI TA KA JU NA

9 = TA KA TE MI TA TA KE TE MI

Konnokol functions as subdivisions as well as possible note groupings within those subdivisions. Of course it is not essential to keep these particular syllable, any other one syllable sounds could be used depending on what one is comfortable with, in that sense one could think in terms of “Konnokols”.

For example, to make it fun in teaching young children, one could use the name of fruits, for a group of 5 “BA NA NA MAN GO” would work just as well as the example above.

So in a broader sense, since we are now a global village one could create “Konnokols” to suit a particular culture or language. Which syllables are used is not so much the point, it’s how we apply them.

When I was learning Konnokol from my teacher Subash, he was not so fussed that I be exact with the actual syllable sounds, as long as I sang the composition correctly. Within the Carnatic system that he teaches, the syllables are important because they relate to actual sounds on three different drums, when you say a specific syllable it correspond to an exact sound on each drum and in this way by learning to sing the composition, the student can learn to play the drum, once he or she has familiarised themselves with the strokes represented by each syllable. Subash’s demonstrated a genius in the sense that he systematized the Konnokol to work on all three drums.

Listen here for an example of sung Konnokol repeated by Ganesh Kumar on Kanjira here

Subash Chandran Ganesh Kumar

All music relates inherently to mathematics and numeric calculations, in South Indian music when musicians all play a passage in unison it is referred to as a “calculation”, usually because it also features a resolution point on the “sum or 1″.

At a theoretical level, I have always had a systematic, somewhat mathematical orientation and approach to music pedagogy. My consideration relative to a more complex approach to phrasing rhythmically was very much in sync with the methods and compositional techniques used within South Indian Carnatic music and so I was somehow lead to discover it.

I was very interested in learning Konnokol and some South Indian composition as a way of boosting or filling up the holes within a Western drumming context of counting, which had not yet innovated a holistic system of counting with an associated musical language. Studying Konnokol inspired me to innovate such a musical rhythmic language elaborating on the “basic” method, structured to function within a Western context associated with the Western drumset. This language which I named “Quornokol” was used in my Master’s thesis to catalogue all possible note groupings existing in subdivisions from 8th to 36th notes.

Even though the Western tradition of communicating musical knowledge is primarily a written notated one, all good drum teachers in the West will emphasize the need to count aloud, my first teacher use to say “if you can count it you can play it!”

Indeed, to try and play a rhythmic phrase one can’t count or sing, by simply reading it is problematic, our voice is our primary musical instrument which our body will follow.

So in pursuing Konnokol studies, I was interested in finding a systematic means that would enable me to count or sing subdivisions from 8th to 36th notes, bypassing all the confusing, and in many cases nonexistent means that relate to counting in the West.

To count anything above 16th notes in our culture has been quite ambiguous, in the sense that a comprehensive agreed to system was not developed, apart from using actual numbers themselves.

Numbers tend to have more than one syllable when spoken, for example “five” or “seven” which makes them inaccurate; while their very nature as numbers and our association with mathematics tends towards a left brain activity when used, which is not optimum for a right brain creative process such as music.

Konnokol is and continues to be an invaluable tool in my musical process. Later this year I will undertake Doctoral studies at Monash university, elaborating on my Master’s thesis which functioned as a general investigation about rhythmic phrasing for all music students and practitioners, while my Doctorate will investigate in specific terms how varied rhythmic phrasing methodologies function within the Western drumset in its context as a musical instrument.

The innovation of the Quornokol instrument within my Master’s thesis fulfilled my pedagogical ambitions towards amalgamating into one process the rhythmic methodologies as they apply to the Carnatic tradition utilising the South Indian Konnokol language, and syncopation as it relates to the Western Jazz tradition utilising the Quornokol language I innovated. The Quornokol instrument achieves this in subdivisions from 8th to 36th notes.

The Quorn.