Ableton Live has carved its own niche within the world of music recording software gaining great popularity with DJ’s and electronic performers. This is due to its work flow features of two different work benches, the session window and the arrangement window, which allows for a different approach to song writing and music production then conventional music production software. As of 2021 Ableton Live is up to its eleventh iteration with "Suite 11", which has brought it into the paradigm of a serious and totally professional music production platform as a Digital Audio Workstation, especially due to its new comping features.

Ableton Live has carved its own niche within the world of music recording software gaining great popularity with DJ’s and electronic performers. This is due to its work flow features of two different work benches, the session window and the arrangement window, which allows for a different approach to song writing and music production then conventional music production software. As of 2021 Ableton Live is up to its eleventh iteration with "Suite 11", which has brought it into the paradigm of a serious and totally professional music production platform as a Digital Audio Workstation, especially due to its new comping features.

Ableton Live’s ability to add random elements in the music making process means one is never locked into one particular arrangement, for both recording and live performances.

This is a great feature that gives Ableton Live a unique edge over its competitors. It's like having software that works like another human musician/producer with you in the studio and on the stage. Indeed there are so many ways one can use Ableton Live.

This has allowed me to do something which I only dreamed of for years but had no way to accomplish. The session window, using launch-able clip boxes within tracks, allowed me to do what has never been done before, and that is to catalogue all note groupings found within the following subdivisions as audio clips:

This has allowed me to do something which I only dreamed of for years but had no way to accomplish. The session window, using launch-able clip boxes within tracks, allowed me to do what has never been done before, and that is to catalogue all note groupings found within the following subdivisions as audio clips:

12th notes (triplets, 7 note groupings)

16th notes (quadruplets, 15 note groupings)

20th notes (quintuplets, 31 note groupings)

24th notes (sextuplets, 63 note groupings)

28th notes (septuplets, 127 note groupings)

32nd notes (octuplets, 255 note groupings)

36th notes (nonuplets, 511 note groupings)

But not only that, it allowed me to organise the note groupings of each sub-division and assign them to drum voices as a way to create drum grooves in all the above subdivisions, enabling me to hear for the first time what grooves could really sound like for instance using 20th notes or quintuplets; as if they were played by a virtuoso drummer who was fully conversant with all the note groupings in that subdivision and could create thousands of groove on its basis.

Frankly in subdivisions above 16th’s, these types of grooves especially utilising 20th notes or quintuplets, 28th notes or septuplets and 36th notes or nonuplets have never been heard in such a comprehensive way. These three subdivisions encompassing odd numbers have not been explored to any significant degree in the West's pantheon of musical traditions like they have been in India's pantheon of musical traditions. This is due to fundamental culture differences of perception about the natural world. The West musical evolution has tended to move and follow a lineage based on aesthetic values with Gregorian chant as its starting point, whereas the East has tended to look at the empirical universe filled with all its mathematical possibilities, and investigate each one and build in its aesthetic premises based on that investigation as an evolving process. Therefore as a result, these three subdivisions have not made their way integrally in today's contemporary music and its associated musical genres, and therefore, generally speaking drum grooves do not really exist on their basis.

Frankly in subdivisions above 16th’s, these types of grooves especially utilising 20th notes or quintuplets, 28th notes or septuplets and 36th notes or nonuplets have never been heard in such a comprehensive way. These three subdivisions encompassing odd numbers have not been explored to any significant degree in the West's pantheon of musical traditions like they have been in India's pantheon of musical traditions. This is due to fundamental culture differences of perception about the natural world. The West musical evolution has tended to move and follow a lineage based on aesthetic values with Gregorian chant as its starting point, whereas the East has tended to look at the empirical universe filled with all its mathematical possibilities, and investigate each one and build in its aesthetic premises based on that investigation as an evolving process. Therefore as a result, these three subdivisions have not made their way integrally in today's contemporary music and its associated musical genres, and therefore, generally speaking drum grooves do not really exist on their basis.

It can be said that within contemporary music genres especially Jazz, Afro Cuban and Jazz Fusion, there are examples of grooves making use of 24th notes or sextuplets and 32nd notes or octuplets, but due to human limitations there is no way that exploration to date can be as comprehensive and thorough as accessing all 63 note groupings in the 24th note subdivision and all 255 note groupings in the 32nd note subdivision as the musical context to create drum grooves.

A human being would be hard pressed to remember all the note groupings in these subdivisions, yet alone be able to play them all flawlessly, which is why most contemporary music predominantly make use of 8th, 12th and 16th notes subdivisions as the basis for music genres and their associated drum groves generally speaking, because the note groupings found in these subdivisions are manageable, since they can be easily remembered, internalised and played by human beings.

I know you will enjoy listening to all these subdivisions as it is rare to hear these kind of drum kit groove in subdivisions of 20th, 24th, 28th and 32nd notes. I have included MP3 examples below that I created in Ableton Live.

Before I get into further elaborations, I wish to explain exactly what I mean by note groupings, let's take 16th notes which has 15 note groupings, what are they ? Well if we count 16th notes as 1 E A U, which is quite a common Konnokol used for 16ths, they would be:

1, E, A, U, 1E, 1A, 1U, EA, EU, AU, 1EA, 1EU, 1AU, EAU and 1EAU

The 16th note subdivision contains 15 note groupings in total:

Four one note groupings

Six two note groupings

Four three note groupings

One four note grouping

The note groupings within each subdivision underpin all the possible rhythmic phrasing and syncopation possibilities within that subdivision and functions as its building blocks. They represent all the colours within that subdivision that allow us to paint rhythmically on any music canvas making use of pulse.

If we were to create dedicated musical notations symbols for every note grouping within most subdivisions it would be possible to create a notation system based on note placement in time as opposed to our current system based on note lengths. This would eradicate 99 per cent of the need for rests in notated music, because all the possible permutations of any kind of rhythmic phrasing are found and expressed within and through the subdivisions groupings. This would mean the note symbol itself would communicate where the note plays on the timeline within the pulse, without having to work that out based on the symbols that came before it. To know where the note starts to play in relation to the pulse seems to me to be the a more foundational consideration; how long it plays for is secondary, you have to know where it starts first of all. The stave indicates pitch so that does not enter into the consideration, and note duration is only really relevant to whole , half and eighth notes in most music. Our notation system in this way could be greatly simplified, since in the current system there are so many different sometimes convoluted ways of writing the same rhythm, but I digress.

So it's easy to see why we have not ventured into groove making possibility with anything above 16th notes generally speaking. A drummer can remember 15 note groupings as with 16th notes, 31 as with 20th notes still doable, but 63 with 24th notes, 127 with 28th notes, 255 with 32nd notes, 511 with 36th notes? Impossible for most people who are not born as geniuses or savants and even then quite unlikely!

So it's easy to see why we have not ventured into groove making possibility with anything above 16th notes generally speaking. A drummer can remember 15 note groupings as with 16th notes, 31 as with 20th notes still doable, but 63 with 24th notes, 127 with 28th notes, 255 with 32nd notes, 511 with 36th notes? Impossible for most people who are not born as geniuses or savants and even then quite unlikely!

Not to mention that subdivisions above 16th notes apart from maybe 32nd notes in isolated instances don’t lend themselves to pop music and that no groove tradition developed throughout history in the West on their basis. There is no such musical genre or style to draw upon that is already firmly lodged in the collective Western psyche, so no music to inspire investigation , no previous reference point to start of from period, which makes beginning such an investigation even more challenging. Not even the south Indian Carnatic tradition immense in its scope has catalogued all these groupings as the basis for its pedagogy of rhythmic grammar!

Even though they do make use of subdivisions above 16th in their compositional structures, and use groupings and numbers and subdivisions in a more complex or holistic way relative to phrasing in general then we tend to in Western popular music; when it comes to 28th notes or just the groupings found in the number 7, the Carnatic system may make use of ten to fifteen variations at most, but certainly not 127.

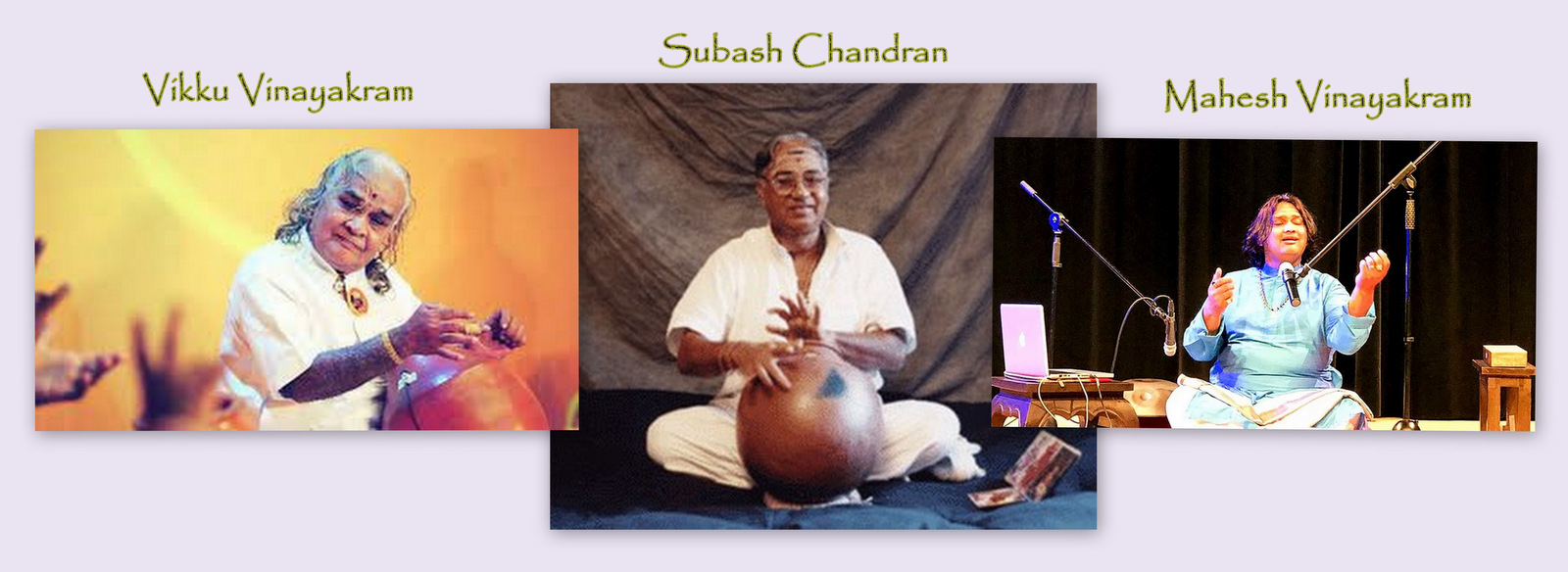

In 2019 I had the very fortunate opportunity to collaborate with renowned South Indian singer/percussionist Mahesh Vinayakram, the son of legendary ghatam player from John McLaughlin's band Shakti, 'Vikku Vinyakram". Vikku is part of one of the most illustrious South Indian musical families and stands with his brother Subash Chandran who was my teacher before passing away in June last year, as primary lineage holders for the Carnatic South Indian Classical musical tradition.

I spent one whole evening with Mahesh when we first met as we travelled in Fiji on our way to play at a retreat sanctuary. I laid out all of my rhythmic research embodied by my Masters thesis, showing him written examples and playing him these recorded drum grooves we are considering here, as well as many actual original works I composed based on this research. His response was that what I had done "was the most comprehensive expose of rhythmic grammar that he had ever encountered in his lifetime". I was completely shocked and honoured by his comment, nothing could be more validating and humbling then to have someone of his musical stature give such feedback about that which I consider to be my life's work.

I spent one whole evening with Mahesh when we first met as we travelled in Fiji on our way to play at a retreat sanctuary. I laid out all of my rhythmic research embodied by my Masters thesis, showing him written examples and playing him these recorded drum grooves we are considering here, as well as many actual original works I composed based on this research. His response was that what I had done "was the most comprehensive expose of rhythmic grammar that he had ever encountered in his lifetime". I was completely shocked and honoured by his comment, nothing could be more validating and humbling then to have someone of his musical stature give such feedback about that which I consider to be my life's work.

In the West subdivisions beyond 16th notes are utilised, in melodies, bass lines, rhythmic comping, as part of solos, but they are not used as the foundation upon which a music genre or style and its associated rhythm section is structured.

On my personal journey as a drummer musician once I had develop sufficiently to start considering how I would teach others, I was always drawn to discover the building blocks, or source codes as I have come to refer to them, that underpin musical traditions and stylistic genres. I figured if I could go to the source and catalogue the rhythmic structures which are inherent in subdivisions and create a system based on them that relates to the drums, that I could impart to my the student a means where they could develop their rhythmic facility and harness a sufficient repertoire to negotiate any stylistic genres of music. So in the 80's I did just that with 12th notes or triplets and 16th notes, but it was not till I undertook my Masters degree that I included all other subdivisions in my investigation up to 36th note or nonuplets.

In order to catalogue all the groupings in these subdivisions, I had to create a way of naming them, to be able to count them. So I created a Konnokol based on single letters, mainly vowels. For examples for 20th notes I used: 1 O E A U.

Once I created the Konnokol for each subdivision I had to work out a system to go about working out what the groupings were and I came across a mathematical relationship between each subdivision which enabled me to verify that I had not left any grouping out of any given subdivision. Once I had done the cataloguing of all the groupings, I had to input them into Ableton Live session window and save each subdivision as a set/project.

Once I created the Konnokol for each subdivision I had to work out a system to go about working out what the groupings were and I came across a mathematical relationship between each subdivision which enabled me to verify that I had not left any grouping out of any given subdivision. Once I had done the cataloguing of all the groupings, I had to input them into Ableton Live session window and save each subdivision as a set/project.

So what was is this groove making process in Ableton Live all about?

The concept structure is as follows:

Four voices = for four way coordination on a drum kit.

To elaborate a little, if we take the 16th note subdivision for example it has 15 note groupings, so I used 15 clip boxes in four tracks totalling 60 clip boxes. Each track representing one of the four limbs of a Western kit drummer was assigned to one percussive voice:

Left foot = cowbell clave

Right foot = bass drum

Left hand = hi-hat

Right hand = snare

This gave me the ability to play any combination of those drum voices as four way coordination. With each clip box having its own play button, by clicking play on one clip box at a time within each track, I could hear all the possible variations. For instance I could have the clave play all quarter notes, the snare just playing 2 and 4, while changing bass patterns over a given static hi-hat pattern.

However one can also create a random element in Ableton Live because one can dictate how each clip box will launch. In other words, once it has played, it can be instructed relative to which clip box will play next in that track, this can be set to: the next one, previous one, first in the track, any, other, none ETC.

In effect I instructed all the moving clip boxes to play randomly for two bar lengths and recorded the process in the arrangement window. What you are hearing with each MP3, is one pass of me pressing play in the session window, having the software play itself by itself, while it also records that performance in the arranger window.

That’s the beauty of Ableton Live I was talking about earlier, you can have some tracks playing in a dedicated way while your drum tracks are playing in a more random fashion for instance, with some of the spontaneity of a human drummer, and that’s not the only way to randomise your project.

So to summarise, the voices I instructed to move are the kick and hi-hat. They move randomly using Ableton Live’s clip launch. Each note grouping occupies one clip box in each track of a particular subdivision, each represents one of four voices of the drum kit. Therefore, it is possible for the program to randomly move within all the note groupings of a given subdivision in all four voices of the conceived kit, as four way coordination.

However in the MP3 examples below, only the hi-hat and bass drum are moving.The changes with the bass drum and hi-hat happen every two to four bars, this allows for some interesting possibilities to be heard (and guys that’s all this is, its just hearing some possibilities, you would not use this as a drum track, because it changes so much). This is just a way of hearing and being exposed to grooves especially in the 20th, 24th, 28th, 32nd and 36th note subdivisions that one will have previously not heard.

I also played with the tempo in different sections in all the examples. The constant voices in every example are two and four on the snare, plus a repeating clave on the cowbell with 12ths, 20ths, 28th, 32nd and 36th notes. One needs a bed to listen against, especially with unfamiliar subdivisions, if every voice was constantly changing, it would be perceptually unrecognisable.

With 12th notes the clave is Afro Cuban.

With 16th notes it just plays quarter notes.

With 24th notes it just plays quarter notes.

With 20th notes it plays notes 1&3 of every grouping of five.

With 28th notes it plays notes 1,3 & 5 of every grouping of seven, since these last two are quite recognisable claves for 5's and 7's, it made sense to use them.

With 32nd notes the clave just plays on the first and third quarter note of every bar.

With 36th notes the clave plays notes 1, 3, 5 and 7 of every grouping of 9.

Also for most of the track with 20th, 28th and 36th notes there is a click track added.

It’s interesting to have the software do the playing, as it would be pretty challenging, to manually move randomly between so many clip boxes even within just two tracks. Especially when you consider 28th notes have 127 note groupings.

Each example below is between 6 and 8 minutes long, but its worthwhile listening at least till the tempo is increased then returns to normal.

Also you may note that the bass drum patterns in the 12th and 16th note subdivisions use different grouping within the bar, while it remains static with a single grouping for the whole length of the bar in the other examples, this is because I was able to add extra content with 12th and 16th notes because the number of groupings within those subdivisions is low compared to 20th, 24th and 28th, 32nd and 36th notes.

So lets hear these subdivisions groove, clicking the link will take you to my Souncloud profile:

12th notes (triplets, 7 note groupings)

16th notes (quadruplets, 15 note groupings)

20th notes (quintuplets, 31 note groupings)

24th notes (sextuplets, 63 note groupings)

28th notes (septuplets, 127 note groupings)

32nd notes (octuplets, 255 note groupings)

36th notes (nonuplets, 511 note groupings)

So how many possible patterns are we talking about here within each subdivision?

Using all the note grouping in each subdivisions played against one another, applied as four way coordination as static one bar patterns would yield:

2401 possible patterns with 12th notes

3375 patterns with 16th notes

29791 patterns with 20th notes

250047 possible patterns with 24th notes

2048383 possible patterns with 28th notes

16581375 possible patterns with 32nd notes

133432831 possible patterns with 36th notes

No one could record all those patterns as audio obviously, much less could a drummer play them, but Ableton did give me the means to catalogue all of them as a potential, by having the possibility of every pattern within all the above subdivisions to be played, while not actually recording it as audio. All the pattern possibilities exist, there, in a kind of stasis or virtual world, waiting for someone to bring them to life by activating the clips.

No one could record all those patterns as audio obviously, much less could a drummer play them, but Ableton did give me the means to catalogue all of them as a potential, by having the possibility of every pattern within all the above subdivisions to be played, while not actually recording it as audio. All the pattern possibilities exist, there, in a kind of stasis or virtual world, waiting for someone to bring them to life by activating the clips.

Only Ableton Live because of how its workflow is structured allowed me to do this and made it possible for me to hear what all those subdivisions really sound like. No one (at least that I’m aware of) has ever catalogued all the note groupings in all these subdivisions, giving them each a name as a means to count them, (which I refer to as Konnokol) and definitely not given the means to hear them through a software based sequencer.

So based on all this, I would love to create a sequencer DAW or plugin package that not only lets you access 3’s, 4’s, 5’s , 6’s, 7’s , 8’s and 9’s as a mouse inputting option, with either notation or a grid; but software that gives you a library ready to go of all the groupings within those subdivisions as a click, drag and drop method into a tracks time line, to create either drum grooves or single note lines. The creative possibilities would become astronomical!

But that’s another story .......... hope you get a lot of inspiration from this post.

All the best, The Quorn.

All the best, The Quorn.